History of the Organization of the National Guard, Part Two

The National Guard's organization during the interwar period through until 1946.

The end of World War One as with all wars, saw a major disbandment of U.S. Army units across all service components. The National Guard, contributing some of the first organized American units sent to France, suffered approximately 43% of all casualties during the war and would be no different in seeing their units stood down in this new peacetime.

In part one I talked about the extensive reforms the National Guard and its Militia predecessor had undergone over the first several hundred years of American Colonial and Independent history. These reforms culminated in the 1903 Militia Act and 1916 National Defense Act, both of which turned the National Guard into a more federally supported professional citizen-soldier force to supplement the Regular Army in times of war.

In what was perhaps the National Guard’s greatest champion of the pre-WW1 era, John McAuley Palmer, a Regular Army officer and son of a Union General, would go onto have a major impact on the future of the organization. Palmer’s father had great respect for the citizen-soldier during the Civil War and the younger Palmer would come to share it after joint manuevers with the guard in the pre-war years, and serving with the 58th Brigade of the 29th Division during the war1. Palmer couldn’t be more different than his assessment of the Guard and how the U.S. should structure its military than Emory Upton. While Upton strongly advocated for a large Regular Army supplemented by volunteers in times of war, Palmer believed that having a strong, well-trained citizen-soldier force during peacetime and could be quickly trained after mobilization would be the most effective solution. In the end, World War One would prove Palmer and his disciples correct versus Upton’s outdated beliefs2. The rise of the industrial age, and with it the invention of automatic weapons, tanks, planes, and long range artillery meant soldiers needed more individual and unit training than at any point in years previous.

The end of war and return of the Guardsman home posed many questions on the future of the Guard, however. In 1919, the War Department recommended to Congress a standing force of 500,000 regulars and 500,000 reservists with no National Guard to speak of - essentially a reversal of the 1916 Defense Act. Thankfully, this plan not only was rejected but caused massive backlash from Congress who would not put up with the cost to pay for such a force. Congress would call upon Guard veteran Senator James Wadsworth to develop a new military policy for the postwar period. Having heard tesitomonials from the famous John O’Ryan and Jack Pershing, the most lasting and remarkable came from Colonel John McAuley Palmer who was serving in the War Plans Divison and an expert on Army organization3.

The back and forth fight would lead to the 1920 Defense Act. This act detailed much of what Palmer recommended and split the Army into three components of multi-tiered readiness and responsibility. Because of those immediate postwar concerns surrounding their future, the National Guard until late 1920 stood at only roughly 60,000 men across the entire United States. After passage and by 1922 that number had ballooned up to 160,000 across all states except Nevada. The new defense act also established the United States into nine Corps areas, each meant to contain one regular, two guard, and three organized reserve divisions for a total peacetime strength of 54 divisions though most not fully manned4.

For its part, the National Guard would contain eighteen divisions, two infantry regiments - one each for Hawaii and Puerto Rico, and a Coast Artillery Corps of approximately 11,600 soldiers. The eighteen divisions would be the 26th-38th, and 40th-45th. The 42nd and 93rd would not return. Also in 1922, the Guard would form four Cavalry Divisions from 21st to 24th and integrate them with various cavalry regiments throughout the country5. 2,200 units in 1,250 towns. authorized strength was 435,800 but never got above 180,000. First tank unit was the 34th Division Tank Company in Duluth, Minnesota in 19206.

With these new structures and organizations, guard leaders would completely revamp training in the 1920s using their experience from the war. As much as possible soldiers were taken out to the field to do hands on training including force on force manuevers, command post exercises, and additional marksmanship training. One of the most impressive feats would be in 1928 in which five different National Guard divisions would train and exercise as a complete unit.

Compared to pretty much everyone else, the National Guard experienced a small boon during the Great Depression due to the draw of stable pay in a time where a quarter of America was out of work. The guard during this period was also seeing 90% or better attendance even with cuts in pay and units even had waitlists full of people wanting to join7. In many cases, the guard also turned into more of a social function for their local communites by proving meeting locations, parades, and various kinds of training to the populace. The flipside of this meant that the Guardsman were considered reliable in enforcing the states laws in quelling domestic unrest such as strikes and protests8. In way too many instances to mention here, the National Guard was called to put down labor disputes amongst factory workers, miners, and longshoremen. This would be a role that would define the Guard throughout the 1950s and 60s usually in the context of race relations and anti-war protests.

Mobilization in 1940

With the Great Depression behind them, a new threat emerged in Europe and the Pacific. By early 1940, the actions taken throughout the 1930s under MacArthur, Craig, and now Marshall and the respective NGB chiefs saw the National Guard sitting at 200,000 soldiers in twenty-two Infantry and Cavalry divisions as well as hundreds of new combat and support units. By contrast, the Regular Army on September 1st, 1939 sat at only 190,000 men, good for 17th largest in the world. Both armies were still mostly equipped as if it were 1919 rather than 1939 and did not look the part of an army ready for what was to come9.

As a result of this new European conflict, President Franklin Roosevelt saw fit to increase the size of the Regular Army and National Guard by a combined 60,000 troops, mostly Guardsman, in order to fill out understrength formations. This also coincided with the number of annual drills increasing from 48 to 60 and annual summer training from 15 days to 21. By the time Hitler had conquered France, the National Guard stood at a historic peacetime high of 242,402 men10. Between 1940 and 1941, this would constitute roughly 76 Regiments for the National Guard. The standard strength of these regiments was raised from 2,542 in 1939, to 3,340 in 1941 but trimmed some as the war went on11.

The next big feat came in late August when Congress allowed the president to call-up the National Guard and Reserves to active duty for a duration of 12 months but despite requesting to be able to deploy them outside of US borders, they would be restricted to the western hemisphere. Three weeks later, the Selective Service Act of 1940 was signed and had massive ramifications for the National Guard. Even before this new law did the Guard see major issues. More than 50,000 Guardsman were released from service due to dependency and pay issues and while that number was quickly made back up, another 40,000 men would be released for defense and agricultural related jobs critical to the security of the nation. The huge turnover in troops in such a short time robbed many units of experienced soldiers and officers when they would be needed most.

Mobilization would present a challenge on its own, though, as many of the bases and camps these divisions would go to were not prepared for thousands of personnel. As with the previous war, units suffered from equipment shortages as many saw their lockers raided to ship to allies via lend-lease. The National Guard Cavalry Divisions would see some of the biggest shakeups as these four were disbanded and instead turned into artillery, antitank, and mechanized cavalry. Draftees would fill out the infantry divisions but also prevented these divisions from working on unit manuevers while also sacrificing many trained personnel to be cadre for new units. A major burden to the National Guard during the mobilization period as well as later during the war would be Leslie McNair, the head of Army Ground Forces and chief trainer of the United States Army in WW2. McNair was not much a fan of the Guard and could be considered Uptonion in nature as a result. Throughout the war, he gave a low opinion of the 30th Division and expressed how guard officers were incompetent and the organization as a whole had done little to contribute to national defense1213. Perhaps the final acts of mobilization before the war came, guardsman would take part in the famous Louisiana Maneuvers in 1941 as well as others in Tennessee, California, and the Carolinas in what was the largest peacetime maneuvers ever assembled. In these maneuvers whole units fought against one another often with missing or substitute equipment while leaders honed their skills in command.

Traingularization of the Army

Starting as early as 1939 the Army under new Chief of Staff George C. Marshall would usher in an entirely new divisional organizational structure. Since World War One, the division was commonly structured in a “square” fashion of two brigades, each with two infantry regiments as well as supporting medical, engineer, and field artillery brigades. Using new standards practiced by the 2nd Infantry Division in 1937, the new structure would be one of “triangular” design14. This organization would utilize everything in “threes” where 3 squads made a platoon, 3 platoons a company, all the way up to 3 regiments of infantry forming a division. This would result in an overall decrease of manpower for the division but was viewed as acceptable as one regiment could be used to fix the enemy, another to maneuver around them, and the third regiment to be in reserve all utilizing new weapon systems and technology compared to that from the previous war. While most of the Regular Army divisions would switch to the new model by 1941, the National Guard wouldn’t completely change until February 194215.

A major effect of triangularization of the divisions meant that many regiments would be booted from the organization and in many case orphaned. Some of these Regiments would stay in the United States or go to U.S. territories in defensive roles such as the 176th Infantry (Virginia Guard) being assigned to defend Washington D.C. or the 138th (Missouri) and 153rd (Arkansas) Infantry being assigned to Alaska. In other cases, these orphaned regiments would become Regimental Combat Teams complete with their own artillery, engineer, and other attachments to become a more self-sustaining unit and used as a “fire brigade” for Corps and Armies throughout Europe and the Pacific. Examples of these include the 156th (Louisiana) Infantry and the 158th (Arizona) Infantry. In one instance, the orphaned 161st (WA State) Infantry Regiment would round out Regular Army’s 25th Infantry Division in the Pacific. Perhaps most famously, the Americal Division was formed entirely from these orphaned regiments on the island of New Caledonia. The regiments were the Illinois NG’s 132nd Infantry, the North Dakota 164th Infantry, and the Massachusetts’ 182nd Infantry along with corresponding support units brought from elsewhere16.

The mostly complete list of NG Separate Regiments includes:

102nd (CT)

111th (PA)

113th (NJ)

118th (SC)

125th (MI)

138th (MO)

140th (MO)

144th (TX)

147th (OH)

150th (WV)

153rd (AR)

156th (LA)

158th (AZ)

159th (CA)

166th (OH)

174th (NY)

201st (WV)

295th and 296th (Puerto Rico)

297th (Alaska)

298th and 299th (Hawaii)

Additionally, there were nine Cavalry Regiments of which all but two became redesignated as Cavalry Groups. The 112th Cavalry (TX) served as a separate regiment under MacArthur’s SWPA and the 124th Cavalry (TX) served in the Burma theater with the MARS Task Force - the successor to Merrill’s Marauders.

World War Two

In the opening shots of World War Two for the United States, the National Guard found itself on the frontline in places like Hawaii and the Philippines17. The Hawaii Territorial Guard’s 298th and 299th Infantry as well as the 251st Coast Artillery all took part in the defense of Oahu on December 7th. In the Philippines, the National Guard had only arrived days before in the form of the New Mexico 200th Coast Artillery Regiment, the 192nd Tank Battalion (companies from Wisconsin, Illinois, Ohio, and Kentucky) and 194th Tank Battalion (companies from Minnesota, California, and Missouri). These Guardsman would fight in Bataan before taking part in the death march and years of captivity under the Japanese. One other unfortunate outcome for a National Guard unit in the early war period was the Texas NG’s 2-131st Field Artillery. On December 7th, the unit was on a ship to the Philippines before being rerouted to Australia and then Java where the whole unit was captured and endured three years of captivity doing forced labor. This particular battalion became infamous as the “lost battalion” due to no one knowing what happened to them until the war ended18.

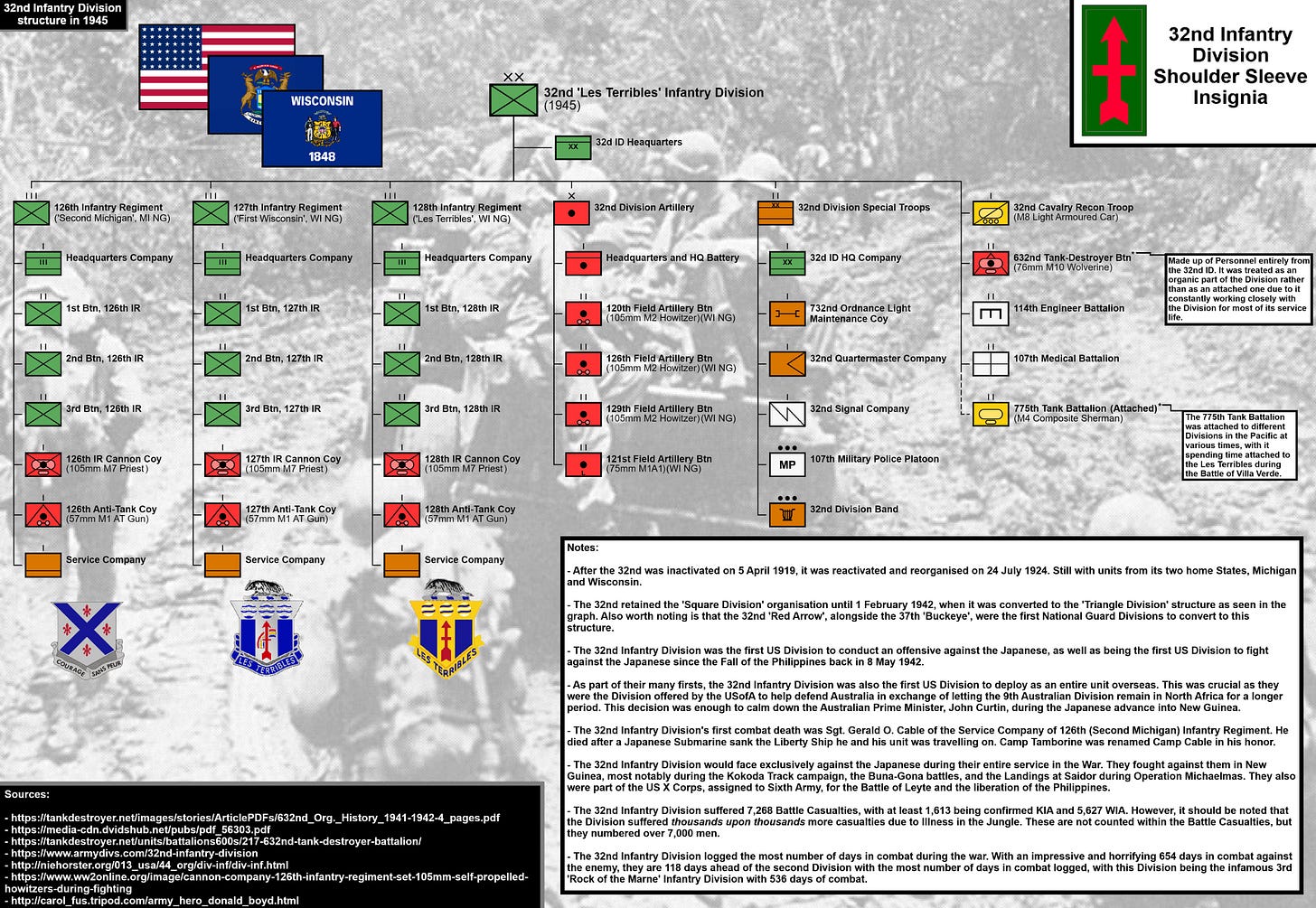

In the Pacific, the National Guard would lead much of the early fight alongside the United States Marine Corps. The 32nd Infantry Division (WI) and 41st Infantry Division (WA/OR/ID/MT/WY) fought like hell through New Guinea while the Americal Division did the same on Guadalcanal and Solomons. The Americal Division would be the first US Army formation to go on the offensive in World War Two. These three would later be joined by the19:

27th (NY)

31st (AL/FL/LA/MS)

33rd (IL)

37th (OH)

38th (IN/KY/WV)

40th (CA/UT/NV)

43rd (CT/ME/VT/RI)

Though overshadowed by the USMC’s excellent propaganda arm, many of these guard divisions would experience more amphibious assaults than their Marine counterparts. The 27th fought alongside Marines in the Gilberts, Marshalls, and Marianas Islands though were constantly ridiculed by the bigoted USMC LTG Holland Smith which led to eventual sacking of the 27th’s commander on Saipan. The 27th would go on to redeem itself late in the war on Okinawa. The rest of these divisions fought under MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area in the Solomons, New Guinea and the Philippines where they constantly led the fight. The guard in the Pacific would see some horrific action in many places and had many casualties of disease, but compared to their brethren in Europe, managed to maintain more of their core state and regional identity and leadership20.

In Europe, the National Guard’s 34th ID (MN/IA/ND/SD) would be the first unit sent overseas, arriving in Ireland in February 1942. The 34th also had the honor of providing the personnel who would go on to become the very first Army Rangers (National Guard Leads the Way hooah). The 34th would be one of the first ashore in North Africa as part of Operation Torch, then later joined by the 45th Division (OK/CO/NM/AZ) in Sicily, and the Texas 36th Division would join up at Salerno in September 1943. These three divisions would fight through every major campaign in Italy and Southern France and suffer some of the highest casualty figures as a result of 2 years of near continuous combat operations. The 45th itself saw over 500 days of combat across Sicily, Italy, France, and Germany including three amphibious assaults, suffer over 20,000 casualties, liberated Dachau, and had one of its longtime members Raymond S. McClain become to only guard officer in World War Two to command a Corps (XIX).

Many of their Guard brethren also saw what can be detailed as an extreme amount of combat in France and the low countries. The 29th Division (VA/MD) rather famously landed on Omaha Beach, the 30th (NC/SC/TN) blunted a German counter-offensive at Mortain which would lead to the Falaise Gap, the 35th (KS/NE/MO) raced across France with Patton, and the 28th Division (PA) would race across France, had the honor of marching down the Champs Élysées during the liberation of Paris, fought on the Siegfried Line before suffering in Huertgen Forest where they gave themselves the nickname "The Bloody Bucket”. The 28th would redeem itself, however, in the Battle of the Bulge where it took the brunt of the initial german offensive while recuperating from earlier battles. Two other NG divisions, the 26th (MA) and 44th (NY/NJ) fought late in the war mostly in Southern Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia. These nine divisions would suffer more than 125,000 losses but take part in some of the most famous and consequential actions of the entire war2122.

Conclusion

1920-1945 was a period of extreme instability across the world. The roarin’ twenties brought great economic boon to the United States while the Great Depression defined the 1930s and World War Two half of the 40’s. No other organization seemed to enjoy this period more than the National Guard in what could be considered their gilded age23. Despite facing clear bias and misunderstandings from Regular Army (and Marine) leaders, the Guard became a legitimized force in the eyes of the public. With new technology and tactics, the Guard would evolve with the Regular Army especially in areas of armored wafare and aviation. In the 1930s and 40s (and beyond but we will get there later), people would look to join the Guard for their consistent pay or to serve with people from the same place as themselves.

In World War Two the guard fielded 18 divisions and a number of independent Infantry Regiments. Half of the divisions served in the Pacific and half in North Africa and Europe. They fought from the very first moment bombs fell on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines in 1941 and were still being engaged by holdouts when the formal Japanese surrender occurred on September 2nd, 1945. As in World War One, the Guard did not carry the majority of the fighting, but their presence and training provided the United States with options. The first two divisions to move overseas were both national guard (32nd and 34th) and it was the existence of these divisions that bought time for draftee-based ones to become trained and organized. As with the previous war, the guard in world war two experienced much disdain from longtime career Regular Army and Marine officers who looked down on citizen-soldiers as lazy, ill-disciplined, and not worthy of the uniform they wore. Time and time again the guard proved them wrong.

As with World War One and the many pieces of legislation originating from the 1903 Militia Act, the National Guard would forever be aligned with the Regular Army in organization and structure. Leaders and soldiers would be trained to similar if not the same standard and equipment would be nominally the same if not sometimes the older model. Despite this, the Guard during the period between 1903 and 2025 will see far more changes than it ever did in the 300 years previous as new technology and equipment come along and units are constantly activated and deactivated.

Sources

Baldwin, Hanson W. “M’NAIR DEPLORES ’WEAK DISCIPLINE.” The New York Times, 1 Oct. 1941, https://www.nytimes.com/1941/10/01/archives/mnair-deplores-weak-discipline-says-in-manoeuvres-critique-that.html. Accessed 2025.

Doubler, Michael D. Civilian in Peace, Soldier in War: The Army National Guard, 1636-2000. University Press of Kansas, 2003.

STANTON, SHELBY L. World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to u.s. Army Ground Forces from... Battalion through Division 1939-1946, STACKPOLE BOOKS, S.l., 2025.

“Marshall Builds the U.S. Army.” Warfare History Network, 19 Sept. 2022, warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/marshall-builds-the-u-s-army/.

Doubler, pg 163

Doubler, 164

Doubler, 164-66

Doubler, 166-67

Doubler, 167

Doubler, 168

Doubler, 169

Doubler, 170

Doubler, 172

Doubler, 173

Warfare History Network

Hanson, yr 1941

Doubler, 175

Stanton, 8

Warfare History Network

Stanton, 184

Doubler, 178

Doubler, 178-179

Doubler, 183

Doubler, 186

Doubler, 183

Stanton, 9-13

Doubler, 188